"Holy Grail" flower scanning robots could revolutionise the wine industry

17 September 2024 | News

Introducing automated 3D scanning robots to vineyards could be the secret to unlocking the “Holy Grail” of the wine industry.

A project utilising Lincoln University viticulturalists and led by the University of Canterbury (UC) aims to develop the robots and use them to get far more accurate yield estimations, which would tell growers exactly how much fruit their vines will bear.

The five-year $6.1 million project is supported by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) Endeavour Fund.

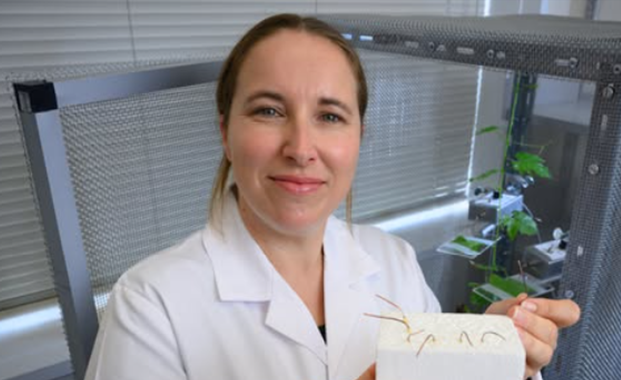

Lincoln University Department of Wine Food & Molecular Biosciences Associate Professor Dr Amber Parker said yield estimation was the “Holy Grail” for viticulture and being able to accurately predict it could be a huge shift for the industry.

Having accurate yield estimation meant growers and winemakers could better prepare for harvest in every step of production. It affected everything, including how much fruit would be harvested, the labour and equipment needed, and what the winery would receive.

“Every step along that chain there’s a financial cost benefit.

“How many tractors do you need? How many drivers? How many people in the winery? How many tanks? Do you need to make changes?”

At present, being within 5-10% yield estimation was considered very good, but still left a huge amount of room for variation.

Part of the problem with determining yield estimates was that growers were working on averages from other years, but the climate fluctuated annually.

Using the autonomous robot, the actual number of fruit on every vine could be measured without supervision, putting growers in a much better position to deal with those fluctuations, Dr Parker said.

The robot estimated yield by creating a 3D scan with the exact number of flower structures on the vines, called inflorescences.

The current method of estimating yield was to count these in person, whether it be visually or by removing samples from the vine.

If you count by observation, you’re guaranteed to miss some.

It was more accurate to remove them, but that meant a loss in potential fruit.

These were expensive, time-consuming processes and could only be used to work out a rough average, as it was impossible to do every vine, she said.

The robots are being designed by a team at UC, led by Professor Richard Green.

The one metre by one metre device zipped down the rows at “a fast walking pace” capturing thousands of images, Prof Green said.

It was loaded with cameras with wide-angle lenses, each taking about 10 pictures per second. The current arrangement featured 12 cameras, collecting images on both sides as it moved through the vineyard.

Those images were then fed into an AI which pieced them together into a highly accurate 3D model of the plant, including everything behind the leaves.

Developing the AI to reconstruct the images was the most difficult part of the process, but now that it worked the result could be revolutionary for the industry, he said.

“We have access to way more information than ever before.”

The technology was groundbreaking, but it was up to Lincoln’s viticulturalists to make sure it could meet the industry’s needs.

We’ve invented a tape measure; they need to tell us what to do with it.

Every few weeks the robot goes through Lincoln’s vineyard scanning the vines. Lincoln’s viticulturalists then collect data manually to compare.

That data was used to determine the practical value the technology had, Assoc Prof Amber said.

They were also looking at the bigger picture, as the 3D images collected provided a lot of data that was previously lacking in the field.

“How we go from flowers to fruits is not really well modelled. Part of the work is can we look at that better and understand that in a predictable power better.”

There was potential for it to be used for other purposes, such as determining vine balance, which estimated how the vegetation was growing in comparison to the fruit.

That information was useful for understanding how the vineyard setup was working and for finding vines that were struggling.

The current method of measuring balance was by weighing the pruned material from the vines, but the robot had potential to provide far more accurate measurements as part of its automated yield scans.

“We have these balance metrics, but they don’t necessarily work well. They’re also quite time-consuming to measure.”

The technology also opened the door for new innovations still to be discovered.

“This is such a high-precision technology. What are the other things that are really important other than yield that we’re scanning that could have value to growers?”

A second robot will soon be deployed in Marlborough in commercial vineyards and this year will be the first full season of testing.