Advocating household climate actions reduces support for more effective policy

04 November 2021 | News

Telling people how to save energy makes them less likely to support government policies on climate change, new research has found.

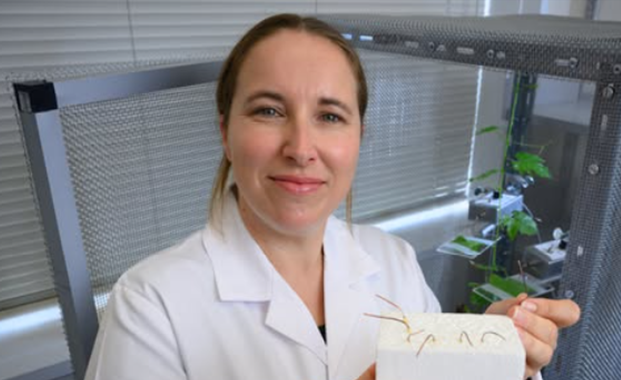

Lincoln University lecturer Dr Jorie Knook was a co-author on Priming for individual energy efficiency action crowds out support national climate change policy with Zack Dorner (University of Waikato) and Philip Stahlmann-Brown (Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research).

The study looked at the crowding out effect, which occurs when people who are encouraged to take one action for the environment are less likely to take or support a second action.

This phenomenon is an issue if household actions, such as changing lightbulbs, reduces support for national climate policy, which has a much bigger potential to reduce emissions than low cost individual actions.

In the survey, half of the participants were asked to think about implementing low-cost energy efficiency measures in their households.

All the participants were then asked about their support for a national policy intervention that reduced emissions from fuel use and would raise the price of petrol.

The results showed a crowding-out effect from individual actions on support for national policy, with lower support among those primed to think about energy efficiency.

The crowding-out effect was strongest among those most worried about climate change.

This suggests that reminding people about individual actions they can take reduced their worry, and made them less likely to support national policy.

Crowding out is not generally considered in the development and implementation of policies, but questions have been raised concerning the probability that the promotion of these actions could undermine public support for more comprehensive policy measures.

The survey was conducted among lifestyle farmers in 2019 as part of the Survey for Rural Decisions Makers, run every two years by Manaaki Whenua. The results were consistent with other studies in other countries, meaning similar results are likely if conducted among urban households.

The authors said the study contributes to an understanding of when and why crowding out occurs in order to help communicate about climate change policy.